The Boyfriend

Benjamin Selesnick

__________

The dining room was one of the larger rooms in Noah’s Atlantic-facing colonial. It had a vaulted ceiling, a glassed-encased display at one end of the cedar-cut table that held a collection of plaques and trophies he’d accrued over the past decade working as the on-call physician for the Celtics, and underneath a glittering chandelier, it had Morris, Noah’s father, who was shifting uncomfortably in his seat. Noah, Morris’s middle-aged son, was pouring wine for everyone at the table. Serving the Kurzweil’s first, then Ira, then his parents, Noah ended with Daniel, finishing the pour with a coy flourish. Daniel raised his glass and flashed his faintly yellowed teeth in thanks. The lone goy, with blonde chest hair poking out from his unbuttoned collar, with murky blue eyes and a pale complexion—Daniel was the evening’s guest of honor. To Morris, an unnecessary guest. A terror, really.

Morris had known Daniel for almost ten years, starting when Daniel and Susan, Morris’s wife, had joined the fundraiser’s board of Boston Children’s Hospital. They’d see one another at the fundraisers that Susan and Daniel hosted, and after Daniel’s wife divorced him, these evenings often ended with Daniel asking Susan for a dance. To this, Susan would smile and nod, before turning to Morris to reassure him that it’ll be quick.

Last week, when Susan told Morris that Daniel would be coming to their Passover seder, Morris was at his computer scrolling through family photos, searching for ones from their trip to Punta Cana. He wanted to find one of him, Noah, and Susan together, back when Noah was still a boy. But he couldn’t find one. He stared at the screen, confused, until he recalled that he spent most of the trip—as with their other Caribbean vacations—either taking long walks on the beach that Noah and Susan didn’t have the patience to join him on, or smoking cigars on their suite’s patio as he reread pulpy novels from his childhood.

When he’d turned to his wife, Susan gave him a hard stare that expressed a lifetime’s worth of frustrations. Morris asked if there was any way she could reconsider. Maybe Daniel could come over on a Sunday to watch some football in the fall? Or join them in the summer at a barbecue with a whole lot of people?

“No,” Susan had said. “It’s time he gets to know everyone.”

So now, with a yarmulke on his head and an empty plate before him, Morris surveyed Noah’s dining room, doing his best not to look at Daniel. The room held many familiar faces. There was Susan, Noah, the Kurzweil’s, and Ira. Harlan Kurzweil had been the head of the urology department at Boston Medical before Morris took his place, a longtime friend and mentor, and Elaine Kurzweil had gotten close with Susan after years of attending the galas Harlan and Morris had dragged them to. Ira’d been friends with Morris and Susan Sirotovsky for almost sixty years, beginning when they were all sophomores at Flemington High. They’d stayed close in the six intervening decades, although their closeness waxed and waned based on their proximity. When Morris took the job at Boston Medical, and Ira took a job as a litigator for a firm in Brooklyn, they all hardly spoke. But when Ira moved to Cambridge five years ago, soon after his wife, Miriam, died, so that he might be closer to his daughter, Linda, and his grandkids, he and the Sirotovsky’s again grew close. He was rotund, dressed in slacks and suspenders, and right now, he was holding court.

“All the maintenance makes me regret buying the place. Ever since I moved into this new house, my days are long with what needs to get done. It’s like my to-do list is eating me. I can never go out and do my shopping, I can’t take my walks. And I hardly know what to do to fix half of what breaks.”

“Uncle Ira,” Noah said, looking at Ira with his large hazel eyes, “I’ve owned this house for fifteen years and I can hardly replace a lightbulb. I have to call for someone to come help with everything. No need to be ashamed.”

“But some shame is good,” Harlan commented. In his retirement, the doctor’s beard had grown long, as had his hair. He’d joked to Morris that he was trying to revert back to an earlier age, an earlier mindset—which the long hair was meant to symbolize—before he had a career and a reputation. “It keeps us honest, and it might keep a few more rooms in your home lit.”

“Some weekend mornings, Linda comes over with the kids to help me keep the house straight,” Ira continued, as if no one else had spoken. “I used to try and make French toast as a treat for them once we finished our work, but I’m no chef. Miriam was always the cook in our house. Until she died, I didn’t know a ladle from a spatula. The French toast ended up being too eggy, too spongy, and the kids would hardly take a bite, no matter how much syrup I poured on it. So now I just warm up some Eggo waffles, because how could anyone, even a schmuck like me, mess them up?”

“And what about you?” Noah interrupted, turning to Daniel, who’d been sitting quietly ever since Susan had rushed him over to the table to take the seat next to her; if left uninterrupted, Ira’s lamenting could go on indefinitely. “Do you have trouble with the upkeep of your place?”

Although Daniel’d been the head of a successful advertising firm in Boston for the backend of his career, he appeared to have lost whatever confidence that kind of work required, because now he spoke softly, like a nervous child being called upon to read aloud in class. “Not really. I downgraded to a smaller place once I retired, so there’s less for me to do.”

“I downgraded, too,” Ira interjected, “but just because a place is small doesn’t mean there isn’t work to do. And the landscaping!—Do you do that yourself?”

“Mostly, but, again, there isn’t much. I live on a small plot near the bottom of mount Monadnock, and I don’t have many neighbors nearby, so I haven’t even really felt the need to keep up appearances.”

“Monadnock?” Harlan cut in. “Isn’t that New Hampshire? Please don’t tell me you drove two hours just for our seder.”

“No,” Daniel answered, shaking his head and holding up a deferential hand. “I was already planning on seeing family in Salem before Susan invited me to your seder.”

With this mention of Salem, Morris’s stomach tightened. Susan had come up with the excuse of Daniel having family in Salem just that morning. “It’s flimsy,” Morris had argued. “If someone asks why he’s there, a random midweek visit to his family won’t be believable. He’ll have to say it’s somebody’s birthday or something, and then we’ll all be ad-libbing.” But as it turned out, nobody had asked until now, and it didn’t seem like Harlan was interested in following up.

“Noah,” Elaine said from across the table, “are we doing this seder?” Like her husband, Elaine had recently taken an aesthetic turn back to her youth: wearing billowing dresses, as she did this night, instead of the prim blouses and pastel-colored khakis she’d worn the past four decades. “I’m getting hungry.”

Noah nodded and slipped into the kitchen. A moment later, he returned with a prepared seder plate and a plate of matzah—rye, as Morris had requested. Once he laid them down on the table, he went into a cabinet drawer by the dining room table and pulled out seven sheets of paper. He gave the pile to Ira and asked him to pass them around.

Morris held out his sheet at arm’s length, so his farsighted eyes could read it. It was a printout of an article titled The Two-Minute Haggadah. It was a couple hundred words at most, and, Morris noted after a quick scan, it was hardly a Haggadah at all. Instead of having the prayer for wine in its original Hebrew, it just said, “Thanks, God, for creating wine,”followed by the instruction, “(Drink wine.)” When it came to listing the ten plagues God inflicted upon Pharaoh and the Egyptians, it said, “Blood, Frogs, Lice—you name it.”The story of Passover was recounted as, “It’s a long time ago. We’re slaves in Egypt. Pharaoh is a nightmare. We cry out for help. God brings plagues upon the Egyptians. We escape, bake some matzoh. God parts the Red Sea. We make it through; the Egyptians aren’t so lucky.” And the rest of it was equally quippy.

“Noah?” Morris cracked. “What’s this two minutes all about? Where’re your real Haggadot?”

Now seated at the head of the table, Noah spoke slowly and in a low voice. His sharp jaw was jutting outwards like a knife.

“Mom told me that tonight we’d be having a guest who isn’t Jewish, so I thought it’d be nice to try doing a seder that would be easier for a non-Jew to understand.”

Morris huffed. Noah’s condescension wasn’t new, but that didn’t make it any less upsetting. Yet, that’s what you get, when you give a boy an easy childhood: the one in Concord with the big house and boarding school and the Ivy League education, followed by the quick admittance to Grossman Medical, the scale tipped by a few calls Morris had made. He’ll think he deserves everything. That surely wasn’t how Morris was raised. Morris’s father had survived the pogroms in Kyiv when he was just a boy, and he’d raised Morris on his own, after Morris’s mom passed in ’48. The man understood perseverance, hard work, making your own way. If he had lived long enough to see who Noah became, who knows what he would’ve thought of him.

“I understand, but that’s not how we celebrate Pesach in this family. Now, Susan,” Morris looked to the seat next to him, where Susan was sitting, “did you bring any of our Haggadot? I think we keep them in the cabinets in the living room.”

Susan looked at him, blanched. In the three years following her seventy-fifth birthday, she’d stopped coloring her hair, so the springy hairs that she was now irritatedly tugging on were silver instead of chestnut.

“I know where they are, Moe, but why would I have brought them? We’re at Noah’s house. He can host the seder however he likes.”

“He can host it so long as it’s Jewish. This,” Morris said, lifting the Two Minute Haggadah, “doesn’t even have a lick of Hebrew on it.”

“Moe, any seder is a good seder,” Harlan said.

Elaine sneered. “Not all seders are good. They’re all boring. They take so long, and whenever I sing Dayenu, it gets stuck in my head for days afterwards. Harlan and I haven’t celebrated in years. The last time I remember having a real seder was when our girls were teenagers.”

“It’s true,” Ira admitted. “I usually don’t have the patience for a realseder, either.”

“But Morris, we can do a real seder, if that makes you feel better,” Daniel said, leaning forward so he could see past Susan, who was seated between the two of them. His tie laid partially on the table, at the edge of his plate, like a snake waiting to pounce. “It’s not a big deal. I’m sure I’ll be able to follow along.”

Don’t act like you care about my feelings, now.If Daniel had cared about Morris’s feelings at all, he wouldn’t’ve come today. If he cared, he wouldn’t be trying to weasel his way into his family. He wouldn’t be making his retirement so hellish.

For the past four months, that is. Up until then, Morris had been enjoying his retirement. With his morning walks into town, and with evenings spent watching CNN with a book of Sudoku puzzles in his hands, he felt like he’d successfully let go of the pent-up stress his career had imposed on him. Susan would even join him on the couch some evenings, reading one of the books she’d bought over the years and had never gotten through. But four months ago, on a cold morning when the wind was whipping freshly fallen snow into the air, Susan had told Morris that, after fifty years of marriage, she was in love with someone else.

“I don’t want to leave you,” she’d said. “I love you just as much as I always have. I love the family we’ve built. But I need to follow this. I am my own person, with my own wants and needs. Some of which you can’t satisfy.”

“Are you talking about sex?” Morris asked. They still had sex, but it was a brief, monthly affair that they’d missed four times last year without mention.

“It’s more than sex. I’ve found a spiritual connection with this other man. He knows me.”

“I thought I knew you.”

“You do know me,” Susan corrected, “but in a different way. I can’t explain it.”

Morris temporarily accepted Susan’s words, but they didn’t make sense. Had she always been capable of cradling two hearts at once? Had she always been capable of such a betrayal? It seemed impossible, since she’d always been so generous with Morris. Back when Noah was a baby, she was always the one who dealt with his late night crying, so that Morris could get some sleep for the lectures he had to teach in the morning. Even when they were kids, attending the same temple—B’nai Keshet, a small temple on a county highway that looked more like a warehouse than a place of worship—Susan would sneak into the synagogue’s kitchen, steal a handful of cookies, and bring them into the sanctuary for the two of them to share.

She’d always made space for Morris’s comfort. How could she take that away now?

In the days following that brief yet firm conversation, Morris’s disposition quickly shifted from unsettled to enraged. Among other things, he couldn’t stop thinking of Susan having sex with this mystery man. Morris imagined him burly, muscled, and a few decades younger than either he or Susan, positioned on top of her in the bed that she and Morris had shared since they bought their home in the late seventies. Then, once he managed to stop thinking of their sex, his mind would drift to an image of them sitting at the kitchen table, Susan across from her lover—faceless, he was always faceless—with coffee in hand. A gentle Sunday morning, they share smiles but not words, as they slowly pick at a muffin.

She was destroying their relationship. Their lives. Soon, Morris started ignoring her. He didn’t tell her where he was going when he left the house. On one sleepless night, his anger even pushed him into creating an eHarmony account. If she’s going to be with someone else, then so will I! He put his information into the site, and was soon given a surprisingly long list of single women aged forty-five to sixty-five—the range he requested—in his suburban area of Massachusetts. He was wowed by his options. He could date an attorney! A chef! Another retiree! A redhead! He was taken with the photos of women who, if he’d seen them in the street, he wouldn’t’ve given a second glance to, and in a feverish rush, he sent a message out to one woman, then to another. My name is Morris. What are you looking for? Have you ever dated a man older than yourself? It was exhilarating. All these different futures were presented before him in the faces of these many women.

But his exhilaration was short-lived, for after being on the site for fifteen minutes, he had the thought that this, the exhilaration, must’ve been exactly what Susan felt when she started seeing her mystery man. Sneaking behind Morris’s back, having rendezvous’s in motels all across New England. With these thoughts, the reality of his situation came rushing back: his wife was growing farther from him with each passing minute, and, even though part of him thought that maybe he should feel differently, he didn’t want to be with any other women. He wanted to be with Susan. Yes, she’d betrayed him in the deepest way, but she was his wife, and they’d been together his whole life. That fact, no matter how badly he might’ve wanted to step around it, could not be understated. Who would ever understand him like she did?

There was still a chance, though, Morris thought, that if he got back in Susan’s good graces, she might dump the mystery man. He couldn’t figure what he’d done to lose her loyalty, but he could still fix this. He deleted his eHarmony account and the next morning picked up a scone for her when he took his walk into town. She didn’t eat it, choosing instead to make herself some toast, but Morris wasn’t deterred. He bought her a necklace and slipped it into her sock drawer later that afternoon when she wasn’t around. On it, he placed a note, short but sweet: I love you. Susan found it when they were readying themselves for bed. Her face, which Morris anxiously watched from his seated position under the covers, remained dispassionate when she lifted the box out of the drawer, when she read the note, and when she opened the box.

“Do you like it?” Morris asked.

“You got me this same necklace for our thirtieth anniversary.” She opened up her jewelry box, which sat on top of the dresser, and pulled out an identical necklace. “Now I have a backup in case I ever lose this one.”

Although dismayed by his own obliviousness, Morris continued with his random acts of affection: he’d compliment her outfits, he’d take her hand in his when they sat next to one another on the couch, he got her a scarf and a pair of satin gloves. But none of this disturbed the graceful stoicism Susan had adopted. And then, without explanation, she started leaving Friday evenings and returning Sunday mornings to see, Morris assumed, the mystery man. She took her toiletries with her, her pajamas. Those private items—some Morris had given her as gifts—left a tremendous absence in their wake that, upon sight, made him feel bereft, ready to shove the plans he’d had for the day in a drawer.

She was planted firm: she was going to have her relationship with this man, and until Morris acquiesced, they wouldn’t be close.

So, despite how painful the thought of Susan being with this other man was, he’d agreed to the new terms of their relationship—as uncomplaining as possible, too, so the transition would be quick and frictionless. Even when Susan told Morris that her boyfriend was Daniel, he said nothing. Yes, later, he’d gone outside and whacked every troubled weed out of their yard with a golf club, but he hadn’t let Susan see that.

And with their new relationship, Morris had also agreed to the idea behind this crazy seder: Morris, Susan, and their loved ones would spend this evening together getting to know Daniel. Nobody in the room outside the three of them knew about his and Susan’s relationship, not even Noah. Susan and Morris agreed that it would be sprung on them at a later point, once they were more comfortable with Daniel. It was a day Morris prayed would never come—but if it ever did come, Morris rested his hopes on the idea that his loved ones would side with him.

Which led to the second reason for why he agreed to have Daniel come to the seder: so he could show himself the better man in front of his loved ones. That way, once word of Susan’s new relationship got out, they might be more inclined to encourage her to stay with Morris, to push her to leave Daniel.

It was a long-shot, admittedly. But at this point, it felt like the only option he had left to save his marriage. In many ways, he thought of this evening as his final stand against the crushing tide.

*

The two-minute Haggadah turned out to be a ninety-second Haggadah, and everyone except Morris seemed happier for it. They breezed through each paragraph, hitting the quips hard, laughing throughout.

“Alright,” Noah said, once everyone had finished their obligatory cup of wine and had stuffed a few corners of matzah into their mouths, “who’s ready for dinner? Mom, want to help me serve?”

“Sure,” Susan answered, and followed Noah into the kitchen. They returned with a plate of brisket, a tray of green beans sitting on a bed of caramelized onions and mushrooms, and a bowl of scalloped potatoes. The delicious smells wafted through the room, reminding Morris of Passover’s past.

“Sue,” Morris said, “did you make all this?”

“They’re my recipes, but Noah made them.”

Putting the food on the table, Noah was beaming. He hadn’t always been a cook, not to mention a good one. He hardly cooked through college, and when he was married, he didn’t cook a thing. Luci, his ex, was the one who did all the work in the kitchen. But soon after their marriage dissolved, Susan started coming over once a week to teach him how to cook, in an effort to support him during that hard time. They spent hours together at Noah’s marbled countertops, prepping veggies, making marinades, sifting flour. Each time they successfully completed a dish, they’d print out the recipe and put it in a binder that Noah kept on his counter for easy reference. By the end of the year, Noah practically had enough recipes to fill a cookbook.

Susan and Noah set the plates down on the table and returned to their seats. Harlan and Elaine quickly reached for the sides, and Morris served himself some brisket.

“Looks good,” Elaine said.

“You’ve got a lot to be proud of, here,” Harlan added.

“But where’s the matzo ball soup?” Ira asked, his hands resting before him on the table. His face, which was so often knit with worry, was now creased with agitation. “I waited all week for it.”

After the table had elected to use the Two-Minute Haggadah, Morris had privately vowed to not get involved with any back-and-forth’s. He knew he’d already lost points with the group for being the old fogey who preferred to stick with tradition. But Ira’s words—so typical, so grating—spurred Morris into speaking.

“Won’t you stop it, Ira? We have a great meal here. Let’s just be thankful for it.”

Ira slouched and averted his gaze, like a battered dog. Looking at the shamed Ira, everyone at the table grew quiet, stiff. The moment weighed heavily in the air, ballooning—until Susan gathered the courage to pop it.

“Next time you come over, I can make you a bowl.” Susan said. “I’ll make a whole pot. You can bring Linda and the grandkids.”

Ira offered an abashed smile, shook his head, and then dove into his meal. Everyone else followed suit. Accompanied by the sound of mouths’ chewing, the candles lit at the start of the seder flickered with a breeze that passed from an opened window. From the corner of his eye, Morris saw Noah watching them all eat, waiting, he believed, for contented looks to appear on their faces.

The first came from Daniel.

“This is wonderful,” he said, wiping his lower lip with a napkin. “I haven’t had brisket since I was in my twenties. I was dating my wife, then. She was half-Jewish,” he motioned with an upturned palm to the table, politely, “and her mom made us a tray of it for Hanukkah. It was the best thing I’d eat for years. I wish I’d asked her for the recipe.”

“Mom’s recipe is right there in the kitchen,” Noah said. “I’ll give you a copy.”

Daniel smiled, and Noah offered one in return.

“Where’s your wife, tonight?” Harlan asked Daniel, from across the table. His eyes were on his plate, as he shoveled a heap of mushrooms onto his fork.

“In Manhattan, I figure. That’s where she moved to after we got divorced.”

“I didn’t know you were divorced. When did that happen?”

“Ten years ago, but don’t worry, it was for the best. She and I had been growing apart for awhile, and then we retired and with all that extra time together we realized that we were ready to move on.”

“Some might say that you both got sick of each other,” Elaine said.

“They wouldn’t be wrong,” Daniel said, laughing lightly. “I think we both got out at just the right time. If we stayed together another week, things could’ve started getting ugly.”

“That’s how it was with my ex, too,” Noah said, speaking as he chewed. “Luci— all of us here knew Luci—She and I had reached the end of our rope by the time we called in the lawyers. If I said one more thing she didn’t like, she would’ve started throwing plates.”

“Your Luci wasn’t like that.” Elaine said, smacking the back of Noah’s palm. “I only met her a few times, but she always treated me like family.”

“You are family—and yes, she could be sweet, if you were lucky enough to be on her good side.”

“But you ended things well, didn’t you?” Ira asked. “Don’t you still talk?”

“Not anymore,” Noah said, “but we had our good times.”

Taking a bite of brisket, tender and riddled with delicious fat, the memory of another meal he and Susan had shared in similar company, easily categorized as the good times, came to Morris’s mind: Noah’s wedding. It was held a mile from Morris and Susan’s home at an old, well-maintained farmhouse that could only be reached by crossing a small bridge over a narrow stream. What Morris remembered clearest from that night was how Noah had looked when he and Luci had their first dance: his eyes gently closed, his freshly-shaven cheek pressed against Luci’s, like he was laying his head against a pillow. True, Noah was already fairly drunk by the time that dance took place, but in his memory, Morris preferred to let that fact slide. All that mattered was his son’s happiness.

Morris still held that position, but his son’s attitude, how mocking and unabashedly self-assured it could be, often blinded him. Even in Noah’s divorce, when Morris wanted to support him, just as Susan had, he couldn’t get past the remarks Noah made when the two of them were alone. “Now I can finally start getting out there again,” he once said. “I’m off the leash.” To that, Morris forced a conspiratorial grin, but he couldn’t force a laugh. A leash. Didn’t he realize just how precious having a partner can be? Didn’t he realize how great it is to be tethered at all?

“And the good times are what matter most, aren’t they?” Morris said. The room had quieted, and Morris thought this an opportunity to reinsert himself. “You can never lose those. They’re always with you. They make it all worthwhile, don’t they?”

Noah tilted his head in mild disagreement and sipped his wine. Morris looked to Susan, hoping that he might find an encouraging smile on her face, but he instead found downturned lips, her chin tucked into her chest as she slowly chewed her potatoes. It read resignation, and when Morris scanned the rest of the table, he found similarly resigned faces. His wan clichés then sank to the floor and faded into the carpeting, like dust.

*

Her name was Charlotte. She had been a nurse at Boston Medical who’d helped Morris during a handful of surgeries back in the early nineties. She was nearly half his age, forty to his sixty, a fact which Morris took little pleasure in. Even when they were alone in his office, lying together on that couch of his that overlooked the methadone clinic five stories below, he disliked her youth. It made him feel old. When they had sex, she had a certain agility, a want, that Morris could never match. Her lust poured, while his only trickled.

Morris’s affair with Charlotte lasted three weeks. It might’ve gone on for longer, had Harlan not popped into Morris’s office one morning before rounds to deliver notes he’d made on an article Morris planned to submit to the medical journal Harlan edited. Instead of finding the office empty, he found Charlotte sitting on Morris’s lap, her scrub top on the ground beside them, the smell of sweat in the air.

“What are you doing?” Harlan yelled. Quick to her feet, Charlotte threw her top back on and tried to apologize to Dr. Kurzweil. He waved her out the door, slamming it as she slipped past him. “What are you thinking?”

“I don’t—”

“Do have any idea what you’re doing?”

Morris knew not to answer his question—not that he had a good answer ready in the first place. He could hardly explain to himself why he’d spent so many early mornings with Charlotte. The sex was great, but had he needed to stray from his marriage? Was he running from Susan?

He didn’t think so. To Morris, his affair with Charlotte existed in a world where Noah and Susan didn’t exist, and therefore, had nothing to do with them. He just wanted to let loose, to feel some excitement. He wanted to see again what it felt like to have someone new fawning after him. It was an experiment, and it in no way spoke to how he felt about Susan.

But with Harlan standing near, hovering above him like a storm cloud, this compartmentalization seemed so thin. How could his affair ever be separate from his home life? If not emotionally—a laughable hypothetical—how could it not physically bleed over? Would he soon be thinking of Charlotte when he slept with Susan? Would he stop having sex with Susan because he was sated with Charlotte? Would Susan notice?

As these thoughts materialized in his mind, predictable ones followed: if Harlan told Susan about Charlotte, she’d leave him, without a doubt; unlike himself, Susan wouldn’t be able to tolerate that kind of betrayal. Then, with his misdeeds public, Noah wouldn’t want to talk to him. He’d always been a momma’s boy. He’d feel betrayed on his mother’s behalf. And without Noah, without Susan, what would be left? Who would he have?

A chill ran through him.

“Please don’t say anything,” Morris said.

Harlan waited a moment to respond. He went over to Morris’s desk and took a seat on it, crossing his legs and hanging his head.

“I won’t lie.”

“You won’t have to,” Morris reassured him. “I’ll end things with her.”

Which he did, suddenly and callously one evening when they were stepping out of the OR—“I can’t do this anymore,” was all he said, before leaving her side and, later, ignoring her calls—but the aftermath of his affair with Charlotte still had its reverberations. He feared aloneness in a way he hadn’t since he was a teenager looking for a date to prom, and the camaraderie Morris had built up with Harlan in the previous decades eroded in part. They still met up for lunch once a month, as they had for years, but Morris could no longer complain about Susan. He tried once, and Harlan had given him an eye. “She’s a good woman,” he’d said firmly. “You’re lucky to have her.”

Standing in Noah’s kitchen beside Susan and Harlan after they’d all finished eating, Morris couldn’t help but think of that brief interaction with Harlan. Would Harlan still say that Susan was a good woman if he knew about her relationship with Daniel? Would he think that Morris deserved this fate, with his affair still undiscovered by Susan? Morris didn’t know, and this uncertainty made his mouth run dry and his palms grow sweaty.

“That boy of yours sure can cook,” Harlan commented, leaning against the counter. Morris wasn’t typically a drink-counter, but he’d noticed that Harlan had taken down practically a whole bottle of wine at dinner, and he was now having another glass. Morris was just nearing the end of his second glass. “Makes you wonder what else he could do if he put his mind to it.”

Susan mhmm’d. Her eyes were elsewhere, sweeping across Noah’s sky-lit kitchen. Near the stove, which was keeping warm a loaf of chocolate babka that Noah had prepared, were Elaine and Noah, talking excitedly. The two of them shared a love for interior design, and over the years, they found a way to make their discussions about it competitive. They’d suggest a design and go back and forth over which celebrity used it and how, its general popularity, and how it fit in with the trends that surrounded it; their answers were cited with articles from the New York Times’ Real Estate section, the Washington Post’s Mansion section, and Town and Country, which they both read religiously. It was impossible to equivocally determine a winner to their arguments, of course, so the unstated victor was decided by who supplied the most points, regardless of their merit, and who spoke with greater conviction.

Across the room, at the island counter, Daniel was getting to know Ira. Of all the people in the room, Morris thought he had the best chance of having Ira take his side if word got out about Susan’s affair with Daniel, since their friendship went so far back, but he also thought that Ira and Daniel had the best chance of hitting it off tonight, among all the people Daniel would meet. Not because they shared many experiences, but because they would likely find common ground through Ira’s ramblings—which seemed to be happening right then. They were standing close to one another, the bulge in Ira’s stomach a few inches from the notches in Daniel’s belt, and they, too, were talking excitedly.

“When Noah graduated from Halworth, I was sure he’d become an architect,” Harlan continued. “I remember that day, his graduation. Noah wasn’t interested in introducing us to the friends he’d made, but in bringing Elaine and I to each building on campus. This was during the whole hubbub after the ceremony. I think you two were chatting with some of the other parents. He took us to the chapel, brought us right under the columns near its entrance, and you know what he said? He said, ‘I wish I could spend every day in a building just like this one.’”

“He probably wanted to spend every day in that chapel because he’d spent half his senior year in its basement with some girl,” Morris said offhandedly. He was looking at Noah and Elaine, who were growing louder. In a flurry, Noah took her by the wrist and led her into the living room. “He got two citations. The dean called us over it.”

“But I do think there was a part of him that wanted to become an architect,” Susan argued, her attention now piqued. Her bony arms were wrapped around her stomach, and her narrow hips shifted slightly from side to side. The floral-printed dress she wore hung an inch below her knees, and it bounced with her shifting. “He loved playing with Legos when he was a boy. He’d spend a whole afternoon making a building as tall as a skyscraper. I think he even took an architecture course in college. But he was always going to become a doctor. He wanted too much to be like his father.”

Morris pshawed. “That’s not true.”

“Oh, it is,” she said, nodding vigorously. “He wanted to be just like you. Becoming a doctor was a way for him to connect with you. It was very important to him.”

“He could’ve connected with me in plenty of other ways. He didn’t need to become a doctor to connect—”

Just then, Elaine barged back into the kitchen with Noah in tow. Her eyes were lit up. “Harlan?” she yelled. “Harlan! Come over here and tell this boy what’s wrong with shabby chic.”

Without missing a beat, Harlan placed his drink down on the counter. “Duty calls,” he murmured, and headed towards them.

The noise in the room swelled and then softened as the Kurzweil’s and Noah left for the living room. Ira and Daniel were still talking, but they were quieter. Their heads had inched closer to one another, like they were each giving confession. Soon, Daniel put a hand on Ira’s shoulder and gave it a small squeeze.

For the first time the whole evening, Morris and Susan were alone. With a foot of space between them, they looked more like strangers lost at a party, than like a couple who’d been together for over fifty years.

“Harlan’s already half in the bag,” Morris said.

“Elaine says that he’s been drinking more recently. She says it’s the boredom.”

Morris pursed his lips in agreement. Then they were silent again. Unlike the silence in the car ride over, which Morris had been fine with, since it meant that he didn’t have to talk about Daniel, this one was excruciating. The seconds stretched longer and longer. How could they ever get around all that divided them? Morris worried. How could he sidestep the space Daniel had taken up at the dinner table, in Susan’s life?

“I know this has been tough for you,” Susan said suddenly, putting a hand on the counter behind Morris’s back. Her voice was a whisper. Morris tensed up. “You know I don’t want to embarrass you or make you feel ashamed in anyway.”

He nodded.

“Your family loves you. I love you. I don’t want you to forget that, no matter what.”

Morris sighed heavily. He never wanted to forget the love they shared, but how could he be expected to remember their love, when, through the day, Daniel’s texts laid unopened on her phone? When she returned home with the smell of his cologne sticking to her skin? How was he supposed to feel comforted by the knowledge of her love, when Daniel was sitting only fifteen yards away from them, talking with his oldest friend?

“I know you love me,” Morris said, “but somedays, it feels like you’re already gone.”

Susan shook her head gently. Then, to his surprise, she wrapped her arms around his chest. As it always had, her head fit snugly under Morris’s chin. In his grasp, she looked like a woodland animal readying itself for a deep sleep.

Staring at the top of her head, Morris felt a rush of emotion, which, of all things, reminded him of how he felt the evening they had their first kiss. They were eighteen then, in the back of Morris’s dad’s station wagon, parked outside of Susan’s house. Her legs were kicked up in his lap, her back comforted by the car’s frame and Morris’s arm. He knew he wanted to kiss her, he knew this was the time, so he braved the space that separated them—but unfortunately, his lips couldn’t reach hers. His stomach twisted into knots, and he squeezed his eyes shut, afraid of the shame that might fill him up if he opened them and caught fear or contempt in Susan’s eyes. Luckily, she quickly made up the distance: She took the back of his head in her hand and used it to pull herself close, to press her lips against his.

“We should take a trip together,” Susan said, looking up at him. “Just you and me. We can go anywhere you want.”

Morris nodded, and grew teary. He lifted his head to take a deep breath, to swallow the sob that was rising in his throat, and saw Daniel and Ira looking in his direction. They looked scared, perturbed by his open expression. They averted their gazes. Then, they got up and left the room. Leaving just Morris and Susan to enjoy each other.

*

The babka came out better than Morris expected. The clean ripples of chocolate that had cut through it like a stream. Steam that had shifted off its top, before dispersing about the middle of Noah’s living room, where the whole group now sat around a glass-topped coffee table: Harlan and Elaine on a couch opposite the couch Noah and Ira shared, Daniel in a reading chair at one end, and Morris and Susan side-by-side on the other. A relaxed drunkenness had fallen over the group, covering them like a shawl. The two couples leaned on their partners; even Noah and Ira were leaning on each other, with Noah’s back resting squarely on Ira’s shoulder.

If the glass table wasn’t so fragile, Morris might’ve kicked his feet on it. Although uncertain of where he exactly stood with Susan, he was still buoyed by relief. That embrace. Susan did love him. He’d never doubted that, but—well, maybe he had. Maybe he’d felt in the weeks leading up to this evening that she loved Daniel more than him. But that couldn’t be true. The five month affair she and Daniel have been having could never compare to the lifetime he and Susan had shared. The embrace they’d shared proved that enough to him.

“Noah,” Ira mewled, as he rubbed a tired hand on Noah’s back. “Have you made up the guest bed?”

“Just before you arrived,” Noah said, with closed eyes. On the table before him was an empty chocolate-dusted plate and an empty glass. “There’s a towel by the bed, too, for the morning.”

Ira nodded, then turned to his side, where Daniel sat. Daniel’s tie was undone, its ends draped over his chest. “Will you be spending the night, too?” Ira asked.

“Maybe if I have another one of these,” Daniel said, smiling, lifting his empty glass. “Speaking of—Noah, I brought a bottle for you. I must’ve forgotten it on my way in. Mind if I go out and grab it?”

“Please,” Noah said.

Daniel got to his feet and headed for the front door. It was heavy, and it boomed when the lock clicked into place.

“Now, that’s a mensch,” Harlan said, jabbing a finger at the door. He was beginning to sound loose, and one eye’s gaze was starting to drift slowly away from the other’s. “Bet he comes back with the best bottle you’ve ever had.”

“He seems very nice,” Elaine added.

“Very nice,” Harlan echoed. “Where’d you say you met him, Susan?”

Morris saw Susan stiffen at the question. There was no lie to tell here, but Susan sat up an inch and cleared her throat as if there were. Morris took pleasure in seeing Susan’s nerves. A just punishment for her poor choices.

“At the fundraiser’s board at the Children’s hospital. He joined not long after I did.”

“I don’t remember you ever making friends there.”

Susan shrugged daintily. She was saved from any follow-up questions, since the front door opened a second later. Daniel walked across the room, bottle in hand, and once he reached Noah, he offered the bottle to him.

“I don’t know much about this bottle,” Daniel admitted. “A friend recommended it to me. He’s an enthusiast, with a wine cellar the size of this room. Nobody knows wine better than him.”

Noah accepted the bottle and twisted it in his hands, scrutinizing the label. Without looking up at him, he put a hand on Daniel’s arm.

“It looks great,” he said. “Could you go grab the bottle opener? It’s in the kitchen.”

Daniel hurried off, then came back a second later. Taking the bottle from Noah, he uncorked it and stepped up to the table.

“Anyone want a refill?”

Glasses were raised. Bending over the table, Daniel refilled Harlan’s, Noah’s, Ira’s, and Susan’s glasses. They each took long sips, and, in satisfaction, leaned back into the cushions behind them. They murmured their compliments, and brought their glasses to their lips for another sip.

Then, last in line, Daniel bent towards Morris.

“How about you, Moe? Want some?”

Morris studied the bottle, then the glass in his hand. It was empty, and had been since he’d eaten the babka. He could’ve gone for more, yet, when he looked up at Daniel’s beckoning expression, he felt a flame ignite in his stomach. Where’d he get off on calling him Moe? Offering him wine in his son’s house?

But, just as quickly as the flame was lit, it was extinguished. Morris was on the path to winning back Susan, after all. He could let this go.

“I’m all set,” Morris said.

Nodding—disappointingly unaffected—Daniel put the bottle on the table and took his seat. The only noise in the room now came faintly from the sound-system: an early Neil Young album that Noah’d put on. Listening intently, Noah’s gaze drifted about the room to the many antiques he’d bought on his trips following the Celtics. Harlan took comfort in Elaine’s shoulder, as she rested her head on his. Susan leaned on Morris lightly, and Daniel, with glazed eyes, was twiddling the ends of one of his shoelaces, pleased and consumed, like a cat with string.

The stillness of the group was broken by Ira. He threw back the last of his glass in a large gulp, lifted Noah off his shoulder, and picked up the bottle for a refill. He studied it, spinning it around in his palms.

“Is this the same bottle you brought to Susan’s the other day?” he asked, turning to Daniel. “I remember this font.”

Daniel dropped his shoelace. He looked over to Susan, who was now looking back at him, closely. He then quickly looked to Elaine, who was also glaring. Morris, who was still somewhat lost in the reverie of the music, had barely digested what was said, and had only mildly registered the room’s flitting eyes.

“No—No,” Daniel said. “It’s a different brand.”

“Oh,” Ira said airily. “I could’ve sworn it was, but what do I know? The bottles all look the same to me—and I like it that way. If I ever reach the point where I can tell one from the other and know how much each costs, I’m in trouble. I have an addictive personality, you know. I was a smoker for thirty years until Miriam and Linda forced me to quit, god bless them.”

Satisfied, Ira put down the bottle and sat back in his chair, at just about the same time Morris sat up. Their words were sinking in. What was this Ira had said about Daniel coming over to his house? When did that happen? Whathappened?

“You were over last week?” Morris said to Daniel. Like it’d been pulled from his mouth, his breath grew short, and his cheeks and ears grew hot. From his side, he felt Susan shrinking on the couch.

“Ye-es,” Daniel stammered. His eyes were down, and the glaze that’d coated them was removed. He darted a look about quickly—at who?—but whatever he saw didn’t change his tone. “It was Monday afternoon. We—”

“It was only for a little while,” Elaine interjected. The worry in her voice was sheathed by pointedness, a typical move of hers when losing an argument. “We had a bottle of wine. Ira was stopping by to see you.”

“I was,” Ira said, his voice weak. “Did I say something—”

“Who else was there?” Morris’s insides was now roiling, and his mind was churning, albeit not very quickly. He could tell that pieces of a puzzle were being laid before him, but he couldn’t sort them out. “Noah, were you there?”

His son had turned and pulled his legs up onto the couch, with the bottom of a foot pressing against Ira’s thigh.

“I was,” he said. “Mom asked me over.”

Morris dropped his head an inch, then another. He wiped a palm across his eyes, and, unwillingly, regrettably, pictured Elaine, Susan, Noah, and Daniel on their back patio last Sunday—on his back patio: Daniel, with his kind and goyish eyes, similar to those that all the mentors Noah had at Halworth had, sitting at the patio table; Noah, dressed neatly in a polo and khakis, as he always was, sitting beside him; Elaine, Susan’s best friend, standing beside Susan in honor; and Susan, at the head of their table, her palms pressed flat against it. What had they said? What had they plotted?

“What were they all doing at our house, Susan?”

Susan shifted further from him on the couch, and pulled her feet up beside her, mirroring her son’s posture. Her eyes couldn’t meet his. Her gaze instead settled on his forehead, right between his eyebrows.

“It was just a small get-together,” she said, failing to sound soothing. “That’s it.”

“A small get together, Sue? But you toldme—you told me—”

Morris couldn’t bear to finish his sentence in front of the party, but the air in the room was sucked out with his unfinished statement nevertheless, for, even though Harlan wasn’t in the know about Daniel, and Ira apparently wasn’t clued in, either, the other four could guess how it would finish: You told me you wouldn’t tell anyone about Daniel.

“Okay, what is going on?” Harlan boomed, finally throwing his hat in the ring. “What did Daniel—?”

“Harlan,” Elaine spat, taking his arm in hers. “Shut up.”

“I didn’t mean to start anything, Moe,” Ira said. “I was just curious about the bottle. That’s all.”

“C’mon, Moe,” Susan said, talking over them all. She put a hand on Morris’s. “Let’s go to the kitchen.”

Susan’s hand, cold and un-calloused, weighed heavily on Morris. He knew better, but all he wanted to do was hold it. When had holding it not brought him comfort? Only twenty minutes ago, when they embraced, when she made that offer to travel together just the two of them, holding her had made him feel whole again, after weeks and months of aloneness. Why wouldn’t it now?

Yet, his hand didn’t move. He couldn’t let it. He couldn’t pretend like they were on the same team—not now, not like he had these past few months.

“Why were they there, Susan?” he finally said. He pulled his hand out from under hers. “Why wasn’t I there?”

“Moe, please,” she said, and again tried for his hand, more gently, her fingers laying on his. “Let’s go. We’ll talk.”

This time, Morris didn’t wait to pull his hand away. He yanked it back and rose to his feet. Standing tall, he looked down at the group, and felt a bitterness coat his tongue.

“You all went behind my back,” he spat.

No one responded, no one moved, no one took their eyes off of Morris—until Susan got up and went towards him. She stepped closer, closer. Looking into his eyes, hers appeared stony, unmoving. The sympathy Morris had seen in them during their embrace wasn’t there anymore.

“Moe, don’t make a—”

“It’s better that it’s out in the open,” Elaine chimed in, before Morris himself could cut Susan off. Elaine was at the edge of her seat, ready to get up and join Susan. “Now you all don’t have to go around hiding.”

“Laney, it wasn’t all of—”

“She’s right,” Noah chimed in, his voice a bit stronger than before. His legs were still folded into Ira’s side, though, and his face held a mixture of guilt and righteousness. “It’s better not to keep secrets.”

“Oh, Noah,” Morris roared, “You don’t get to—”

And then, the last voice that should’ve chimed in did.

“We don’t have to talk about it, everyone,” Daniel said to the group. “We can wait until Moe’s ready. We shouldn’t rush him. This is a lot. Moe,” he looked at Morris, “we’re here whenever you’re ready.”

Daniel got to his feet, wobbled a bit, and stepped towards the fractured couple. To be the mediator, Morris supposed, to separate the two of them in case one of them—Morris, no doubt—did something they might regret. The path between him and the couple was narrow, blocked by the ends of his chair and the coffee table. Had he been sober, this would’ve been easy to traverse, but with his tipsiness, it was trouble: a toe of his got caught as he lifted a foot to cross a corner of the coffee table. He teetered, leaning forward, and reached out to Morris—the nearest person—hoping he’d grab him and keep him from falling forward.

Time slowed rapidly, then. Instinctually, Morris knew that the expression on Daniel’s face was one he would never forget: his eyes bright, his mouth slightly agape, his gaze trained on Morris. All else surrounding him would evaporate with time, but the face would remain.

It was the smallest movement. Small enough that, if Morris really wanted to argue, he could claim it didn’t happen at all. Instead of reaching out to catch the hand Daniel stretched towards him, or just letting his hand catch Morris’s shoulder, Morris twisted his chest out of the way. Just a tiny twist, a few inches at most. He didn’t even have to think about it. Just seeing Daniel so panicked, so vulnerable—his body made the choice itself.

And so, Daniel fell: He extended a hand to catch himself—Not on the ground, though, but on the glass coffee table, since that’s where he was falling. As if breaking the surface of a pond, Daniel’s hand crashed through the glass, the heel of his palm leading the way. On top of a few glittering shards, Daniel’s palm hit the floor, then his shoulder, as he turned to the side to protect himself. His head skimmed the shattered rim of the table, his feet hit the opposite rim, jutting them upwards. The remaining glass shards around the table’s edge continued to rain down, until they all sat on the floor, beside Daniel’s dazed body.

Time slowed even more, now, to a near stop. The moment captured as if in a jar, so Morris could study it later, when his doubts arose, which they often would in the coming weeks. On the evenings he spent alone in his house, pacing the kitchen, waiting for dinner to magically appear out of nowhere; when he surfed potential matches on Match and E-Harmony. He would think back to this moment and wonder why he had let Daniel fall into the coffee table. Why couldn’t he have just caught him? He could’ve sucked up the embarrassment of learning about Susan’s betrayal that evening and worked things out later, couldn’t he?

But then he would remember how the moment unfurled: how the group jumped to the floor to tend to Daniel, who had quickly reoriented himself and showed that he was unharmed, except for a small bump on his head and some thin cuts on his hands; how, after securing that Daniel wasn’t stunned or seriously injured, Susan had looked at Morris in such fury; and how he had looked back at her and felt the same fury. Her heart was more with Daniel than with him. That enough was now clear to him.

And he would remember how he felt the next morning, when Susan returned home after spending the night at Noah’s and told Morris why she’d let slip the secret of her relationship with Daniel. “Elaine’s my best friend,” she said. “I needed to talk about Daniel with somebody. And it felt unfair to have Noah spend time with this man and then later tell him that he was actually his mother’s boyfriend. Imagine how blindsided he would’ve felt.” Morris knew that, with this brief explanation, Susan hoped that he’d regret letting Daniel fall. But he didn’t. In fact, hearing her speak so plainly of her justifications for her actions only made him feel more resolute.

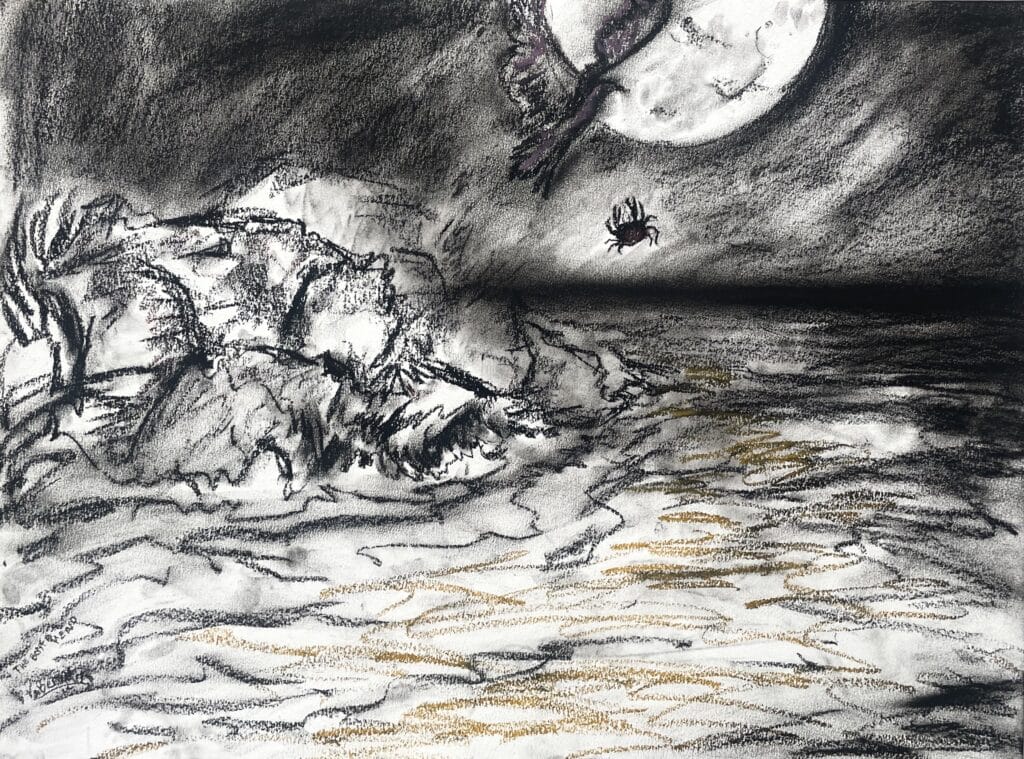

And yet—and yet. Through all this internal back-and-forth, what he remembered best on those lonely evenings was what he saw when he stormed out of his son’s house, on that first night of Pesach. Alone, on the sidewalk, he looked out at the Atlantic, its surf knocking against the pewter-colored rocks that struck a few dozen yards out into the water, and he spotted in the darkness a gull fly down from the sky to pick up a crab traveling across those rocks. The gull rose a dozen feet, its beak pointed towards the moon, but it quickly dropped the crab, whose stiff shell was too slick to hold. Hurtling, the crab’s claws churned slowly, until it crashed into a crumbling wave, subsumed by the tide.

__________

Note. ‘The Two-Minute Haggadah’ was written by Michael Rubiner and published by ‘Slate’ on March 25th, 2013.

__________

Benjamin Selesnick lives and writes in New Jersey. His work has appeared in decomp, Lunch Ticket, SFWP Quarterly, and other publications. He holds an MFA in fiction from Rutgers University-Newark.

__________

To learn more about submitting your work to Boudin or applying to McNeese State University’s Creative Writing MFA program, please visit Submissions for details.

Posted in Boudin 2022, Boudin September '22 Edition and tagged in #BenjaminSelesnick, #September'22Edition, #boudin, Fiction